What did Watson and Crick contribute to genetics

T he wave of protest that followed Sir Tim Chase'south stupid comments nearly 'girls' in laboratories highlighted many examples of sexism in science. I claim was that during the race to uncover the structure of DNA, Jim Watson and Francis Crick either stole Rosalind Franklin's data, or 'forgot' to credit her. Neither suggestion is true.

In April 1953, the scientific journal Nature published 3 back-to-dorsum articles on the construction of DNA, the material our genes are made of. Together, they constituted one of the nigh important scientific discoveries in history.

The get-go, purely theoretical, article was written past Watson and Crick from the University of Cambridge. Immediately following this article were two data-rich papers by researchers from Male monarch's Higher London: one by Maurice Wilkins and two colleagues, the other by Franklin and a PhD student, Ray Gosling.

The model the Cambridge duo put forward did not just depict the DNA molecule as a double helix. It was extremely precise, based on complex measurements of the angles formed by different chemic bonds, underpinned by some extremely powerful mathematics and based on interpretations that Crick had recently developed equally role of his PhD thesis. The historical whodunnit, and the claims of data theft, plow on the origin of those measurements.

The 4 protagonists would make proficient characters in a novel – Watson was immature, brash, and obsessed with finding the structure of DNA; Crick was brilliant with a magpie mind, and had struck upwards a friendship with Wilkins, who was shy and diffident. Franklin, an expert in X-ray crystallography, had been recruited to King's in late 1950. Wilkins expected she would work with him, but the head of the King'southward group, John Randall, led her to believe she would be independent.

From the outset, Franklin and Wilkins only did not become on. Wilkins was quiet and hated arguments; Franklin was forceful and thrived on intellectual debate. Her friend Norma Sutherland recalled: "Her manner was brusque and at times confrontational – she aroused quite a lot of hostility among the people she talked to, and she seemed quite insensitive to this."

Watson and Crick's outset foray into trying to crack the construction of Dna took identify in 1952. Information technology was a disaster. Their three-stranded, inside-out model was hopelessly wrong and was dismissed at a glance past Franklin. Following complaints from the King'southward group that Watson and Crick were treading on their toes, Sir Lawrence Bragg, the head of their lab in Cambridge told them to end all work on DNA.

However, at the beginning of 1953, a US competitor, Linus Pauling, became interested in the structure of Dna, so Bragg decided to set up Watson and Crick on the problem over again.

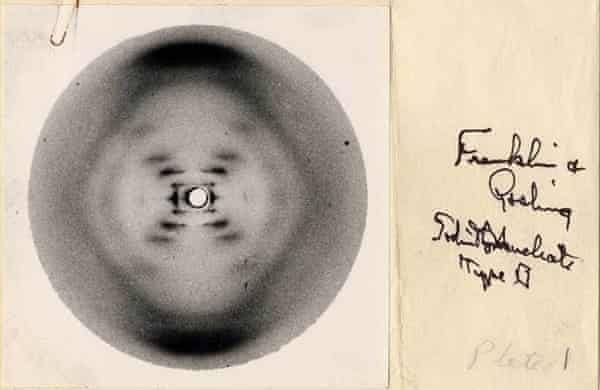

At the stop of January 1953, Watson visited King's, where Wilkins showed him an Ten-ray photo that was later on used in Franklin's Nature article. This image, often called 'Photo 51', had been made past Raymond Gosling, a PhD student who had originally worked with Wilkins, had so been transferred to Franklin (without Wilkins knowing), and was now once again being supervised by Wilkins, as Franklin prepared to leave the terrible atmosphere at Male monarch's and carelessness her work on DNA.

Watson recalled that when he saw the photo – which was far clearer than any other he had seen – 'my mouth fell open and my pulse began to race.' Co-ordinate to Watson, photograph 51 provided the vital clue to the double helix. But despite the excitement that Watson felt, all the primary issues, such as the number of strands and higher up all the precise chemical organisation of the molecule, remained a mystery. A glance at photograph 51 could not shed any calorie-free on those details.

What Watson and Crick needed was far more than the idea of a helix – they needed precise observations from X-ray crystallography. Those numbers were unwittingly provided past Franklin herself, included in a brief breezy report that was given to Max Perutz of Cambridge University.

In February 1953, Perutz passed the study to Bragg, and thence to Watson and Crick.

Crick now had the material he needed to do his calculations. Those numbers, which included the relative distances of the repetitive elements in the DNA molecule, and the dimensions of what is chosen the monoclinic unit cell – which indicated that the molecule was in two matching parts, running in opposite directions – were decisive.

The report was non confidential, and in that location is no question that the Cambridge duo acquired the data dishonestly. However, they did not tell anyone at King's what they were doing, and they did not enquire Franklin for permission to interpret her data (something she was especially prickly almost).

Their behaviour was cavalier, to say the least, but there is no show that it was driven past sexist disdain: Perutz, Bragg, Watson and Crick would have undoubtedly behaved the same fashion had the information been produced by Maurice Wilkins.

Ironically, the information provided past Franklin to the MRC were nigh identical to those she presented at a modest seminar in King's in fall 1951, when Jim Watson was in the audience. Had Watson bothered to take notes during her talk, instead of idly musing almost her dress sense and her looks, he would have provided Crick with the vital numerical evidence 15 months earlier the breakthrough finally came.

By take chances, Franklin's data chimed completely with what Crick had been working on for months: the type of monoclinic unit of measurement cell institute in DNA was likewise present in the horse haemoglobin he had been studying for his PhD. This meant that Dna was in 2 parts or chains, each matching the other. Crick'due south expertise explains why he quickly realised the significance of these facts, whereas information technology took Franklin months to get to the same point.

While Watson and Crick were working feverishly in Cambridge, fearful that Pauling might scoop them, Franklin was finishing up her work on Deoxyribonucleic acid before leaving the lab. The progress she made on her ain, increasingly isolated and without the benefit of anyone to exchange ideas with, was only remarkable.

Franklin's laboratory notebooks reveal that she initially constitute it difficult to interpret the outcome of the complex mathematics – like Crick, she was working with zip more than than a slide rule and a pencil – but past 24 February, she had realised that DNA had a double helix structure and that the fashion the component nucleotides or bases on each strand were continued meant that the 2 strands were complementary, enabling the molecule to replicate.

Above all, Franklin noted that 'an space variety of nucleotide sequences would exist possible to explain the biological specificity of DNA', thereby showing that she had glimpsed the most decisive surreptitious of DNA: the sequence of bases contains the genetic code.

To show her bespeak, she would have to convert this insight into a precise, mathematically and chemically rigorous model. She did non get the gamble to exercise this, because Watson and Crick had already crossed the finishing line – the Cambridge duo had rapidly interpreted the double helix structure in terms of precise spatial relationships and chemic bonds, through the construction of a concrete model.

In the middle of March 1953, Wilkins and Franklin were invited to Cambridge to run into the model, and they immediately agreed it must be right. It was agreed that the model would be published solely as the work of Watson and Crick, while the supporting information would be published by Wilkins and Franklin – separately, of course. On 25 April there was a party at King'south to gloat the publication of the three articles in Nature. Franklin did not attend. She was now at Birkbeck and had stopped working on DNA.

Franklin died of ovarian cancer in 1958, iv years earlier the Nobel prize was awarded to Watson, Crick and Wilkins for their work on DNA structure. She never learned the full extent to which Watson and Crick had relied on her data to make their model; if she suspected, she did not express whatsoever bitterness or frustration, and in subsequent years she became very friendly with Crick and his wife, Odile.

Our motion-picture show of how the structure of Dna was discovered, and the myth most Watson and Crick stealing Franklin'due south information, is almost entirely framed by Jim Watson's powerful and influential memoir, The Double Helix. Watson included frank descriptions of his own appalling mental attitude towards Franklin, whom he tended to dismiss, even down to calling her 'Rosy' in the pages of his book – a nickname she never used (her proper name was pronounced 'Ros-lind'). The epilogue to the book, which is often overlooked in criticism of Watson's attitude to Franklin, contains a generous and fair clarification by Watson of Franklin'south vital contribution and a recognition of his ain failures with respect to her – including using her proper name.

It is articulate that, had Franklin lived, the Nobel prize commission ought to have awarded her a Nobel prize, as well – her conceptual understanding of the structure of the Dna molecule and its significance was on a par with that of Watson and Crick, while her crystallographic data were every bit good as, if not better, than those of Wilkins. The uncomplicated expedient would have been to honour Watson and Crick the prize for Physiology or Medicine, while Franklin and Watkins received the prize for Chemistry.

Whether the committee would accept been able to recognise Franklin's contribution is another matter. As the Tim Hunt affair showed, sexist attitudes are ingrained in science, as in the rest of our civilisation.

Matthew Cobb's Life's Greatest Hugger-mugger: The Race to Crack the Genetic Lawmaking is published past Profile Printing.

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/science/2015/jun/23/sexism-in-science-did-watson-and-crick-really-steal-rosalind-franklins-data

0 Response to "What did Watson and Crick contribute to genetics"

Post a Comment